Who is, or has been, the biggest influence on your art

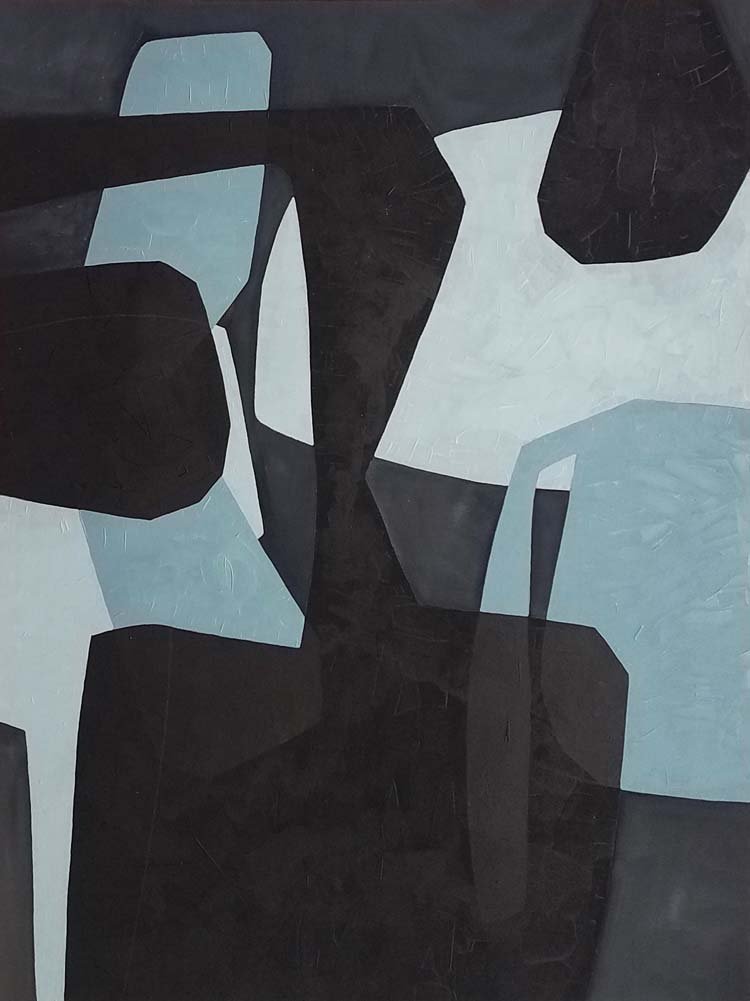

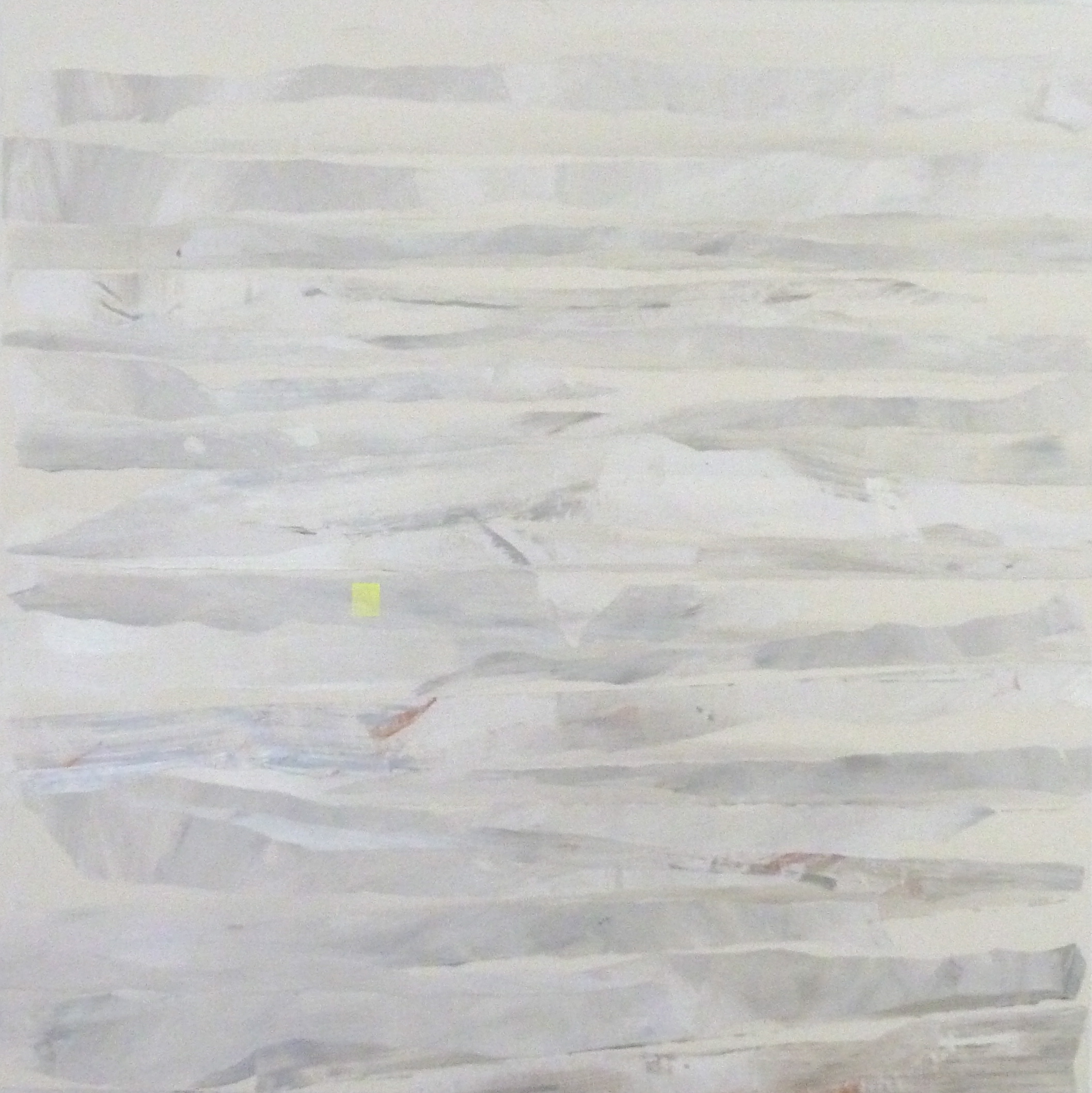

Many years ago, I rounded the corner in the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas and was confronted by Franz Kline’s Black and White Number 2. The powerful contrast between of the work stopped me flat. But as I slowly approached, the various layers of white and the the detailed brush stroke revealed a much more complex, intimate work. The art was very human to me. From a distance, it appeared simple, easily judged. But close up, it revealed the complex nature of its being. It was, as I like to say, my first real “art attack.”

What inspired you to study to become an artist?

To me art is primal. It is a gut reaction to what I see. I look for that reaction in the work of others and I seek to create it in the work of my own. The addiction to that reaction is what motivated me to start creating art.

How long have you been working with your medium?

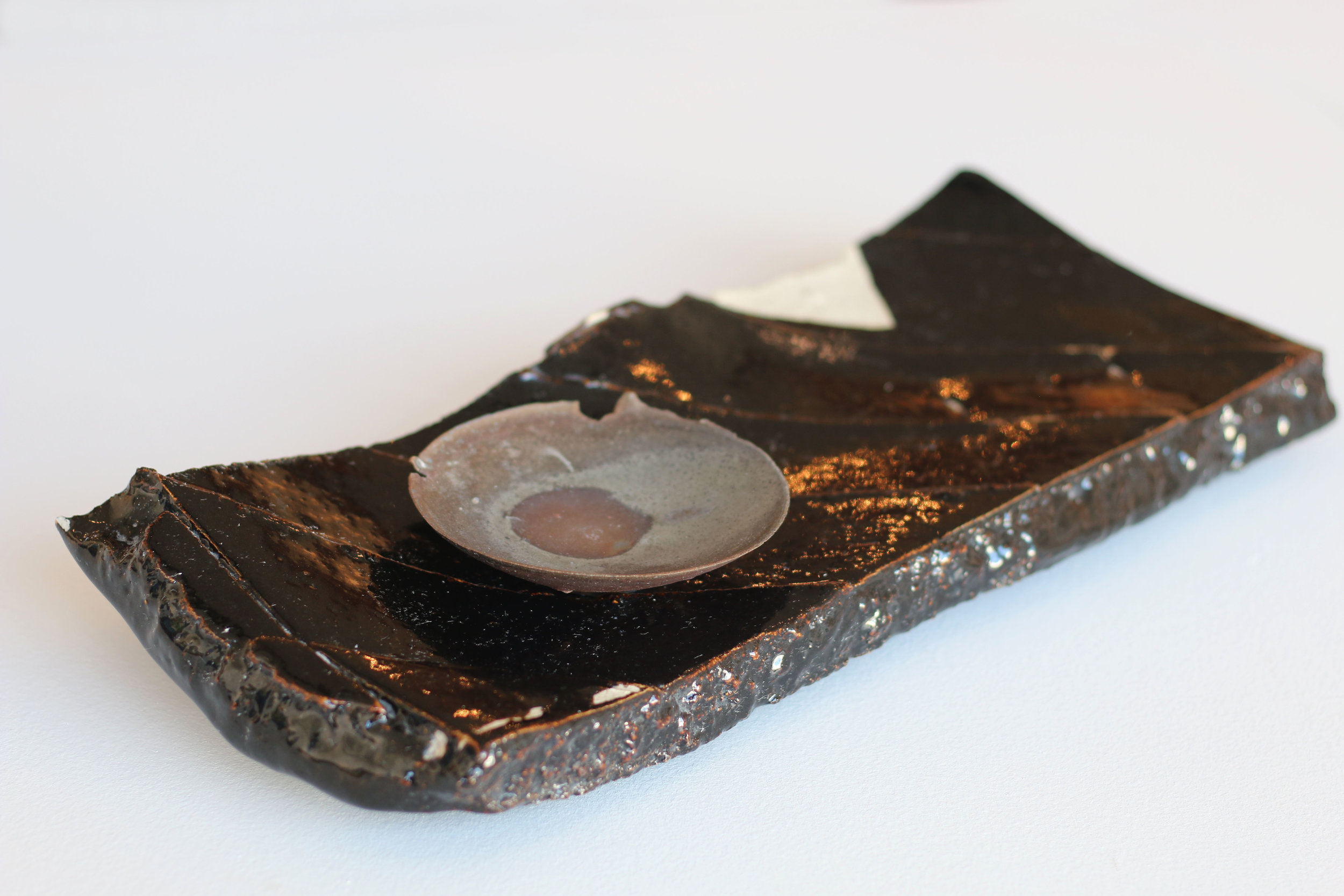

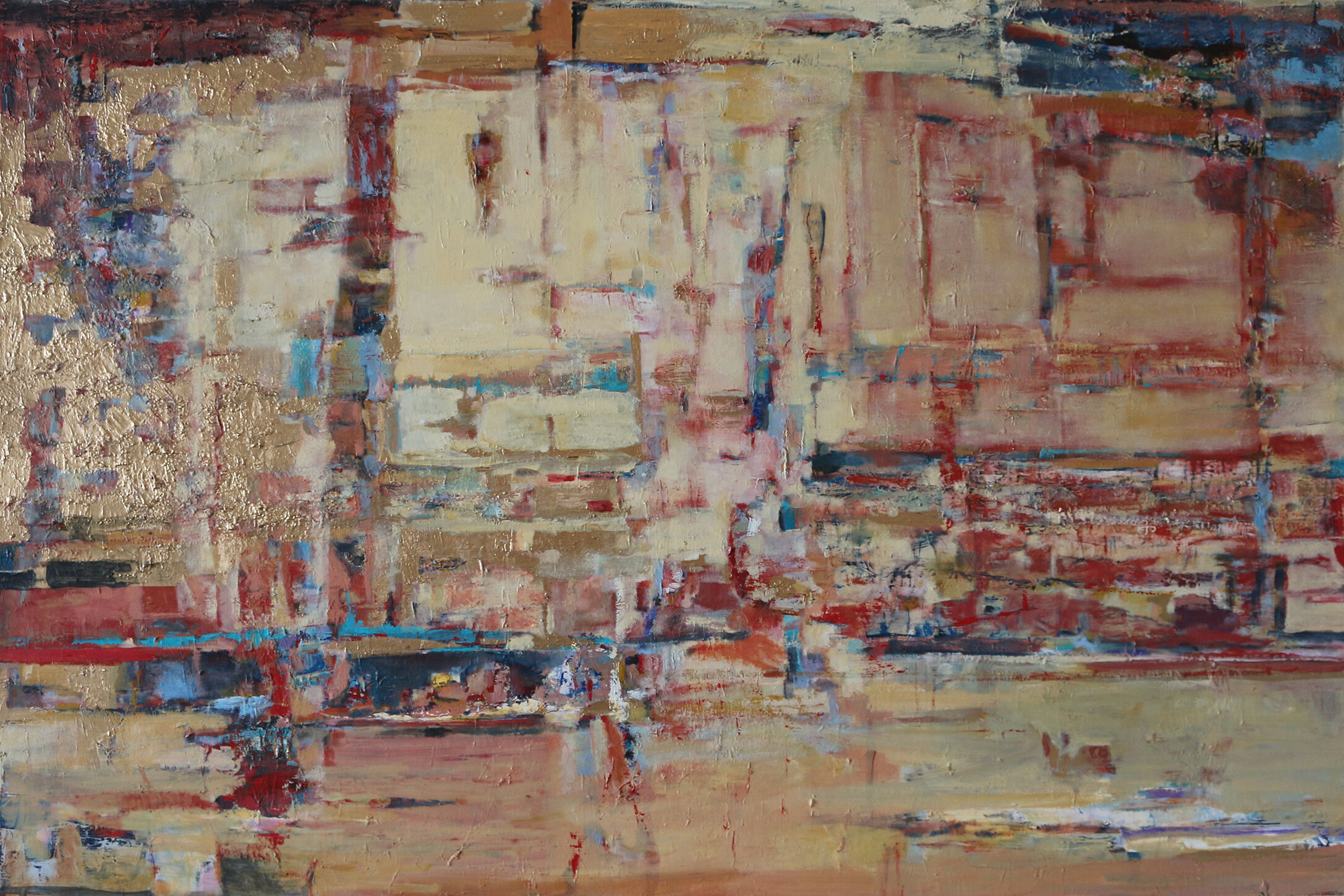

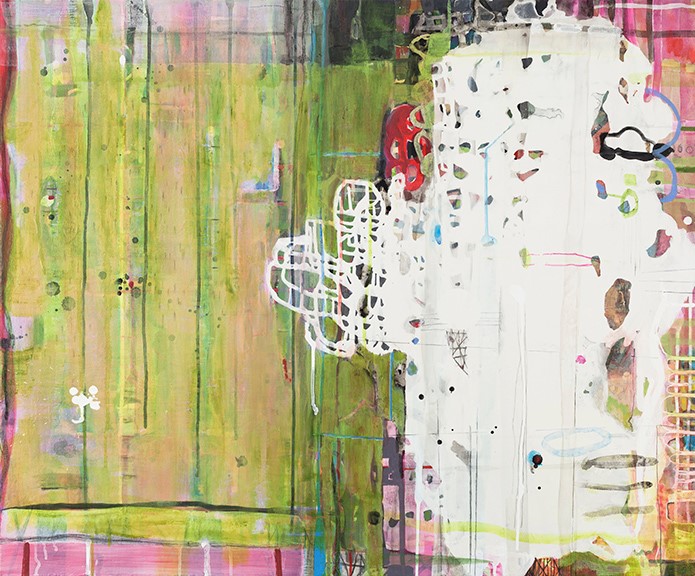

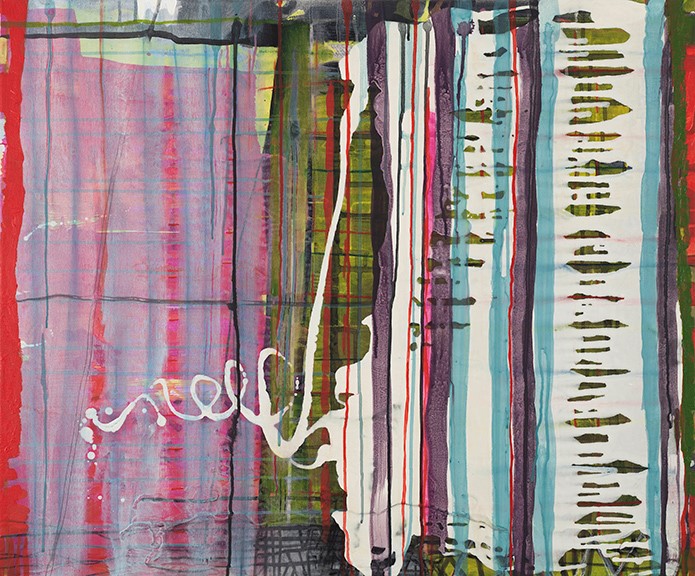

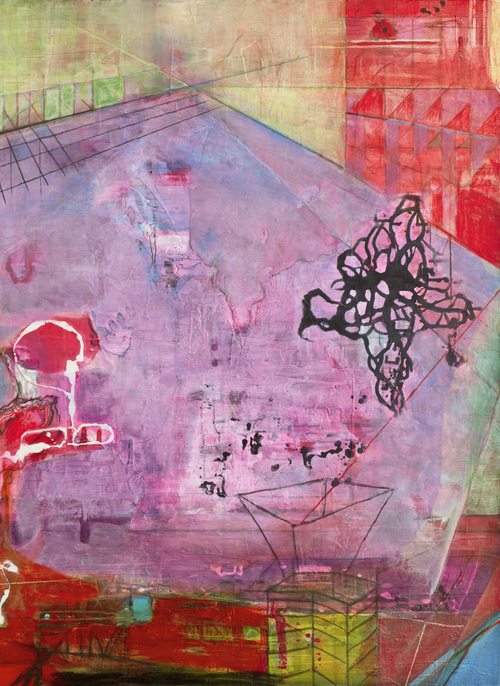

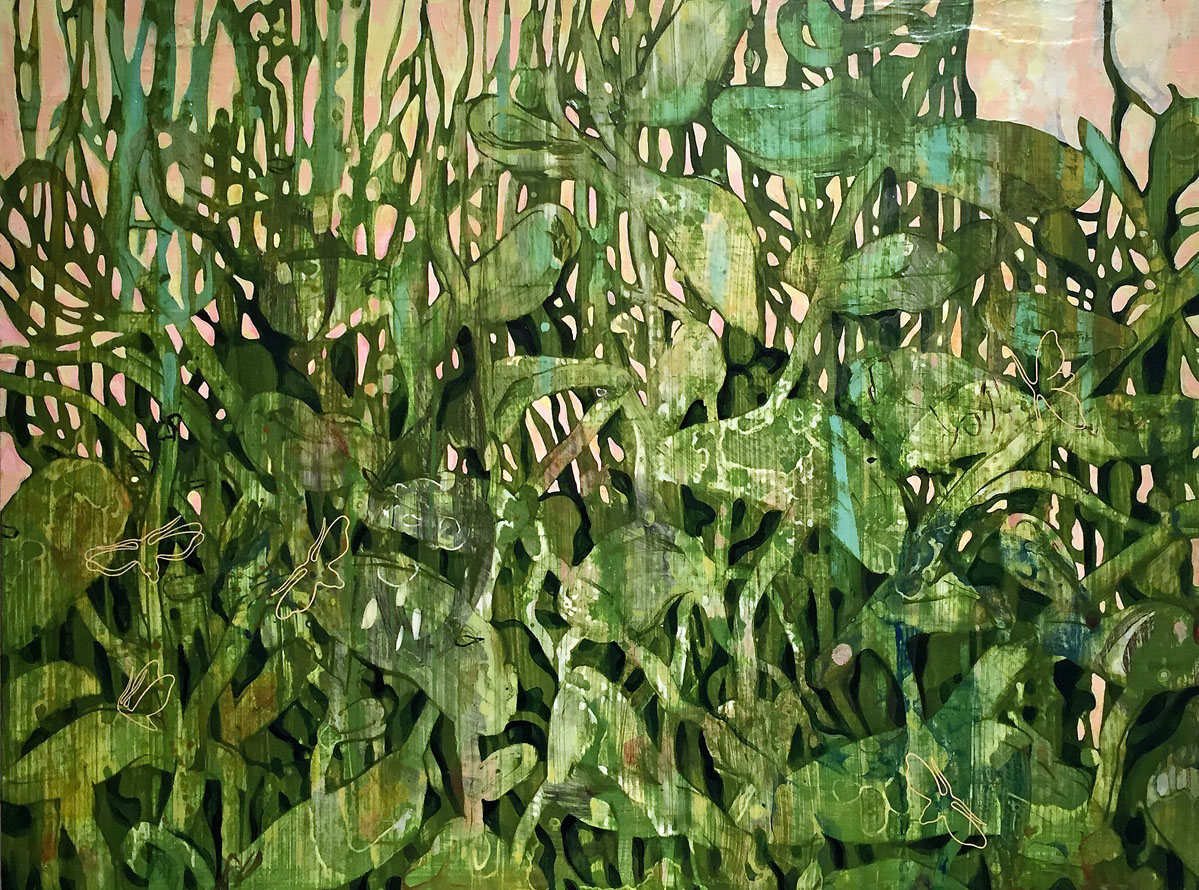

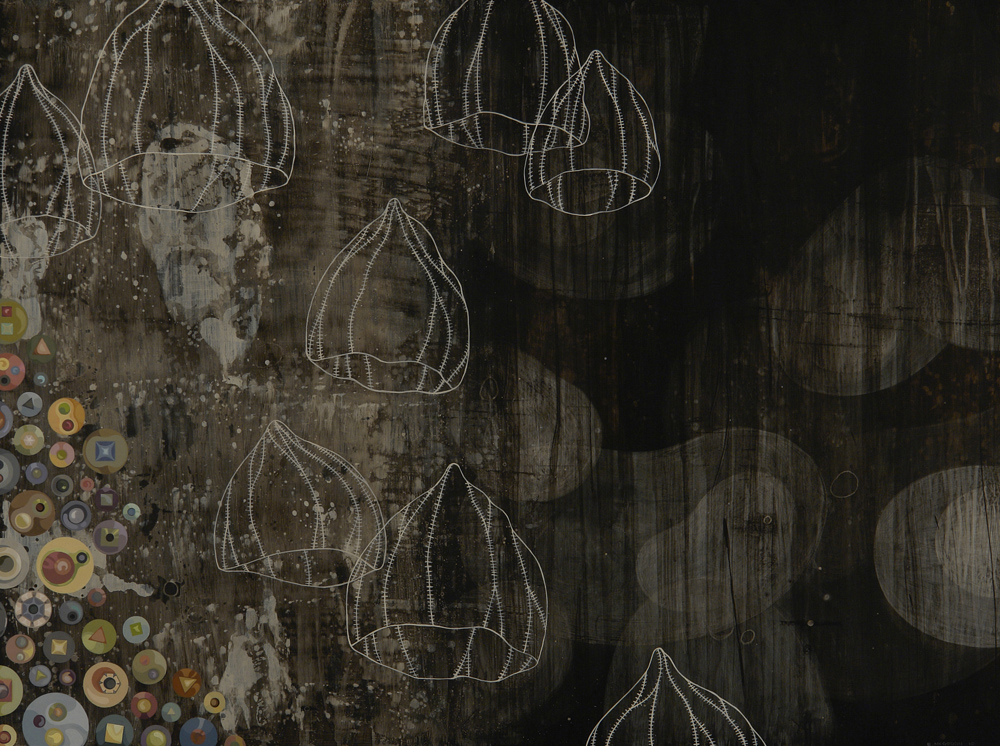

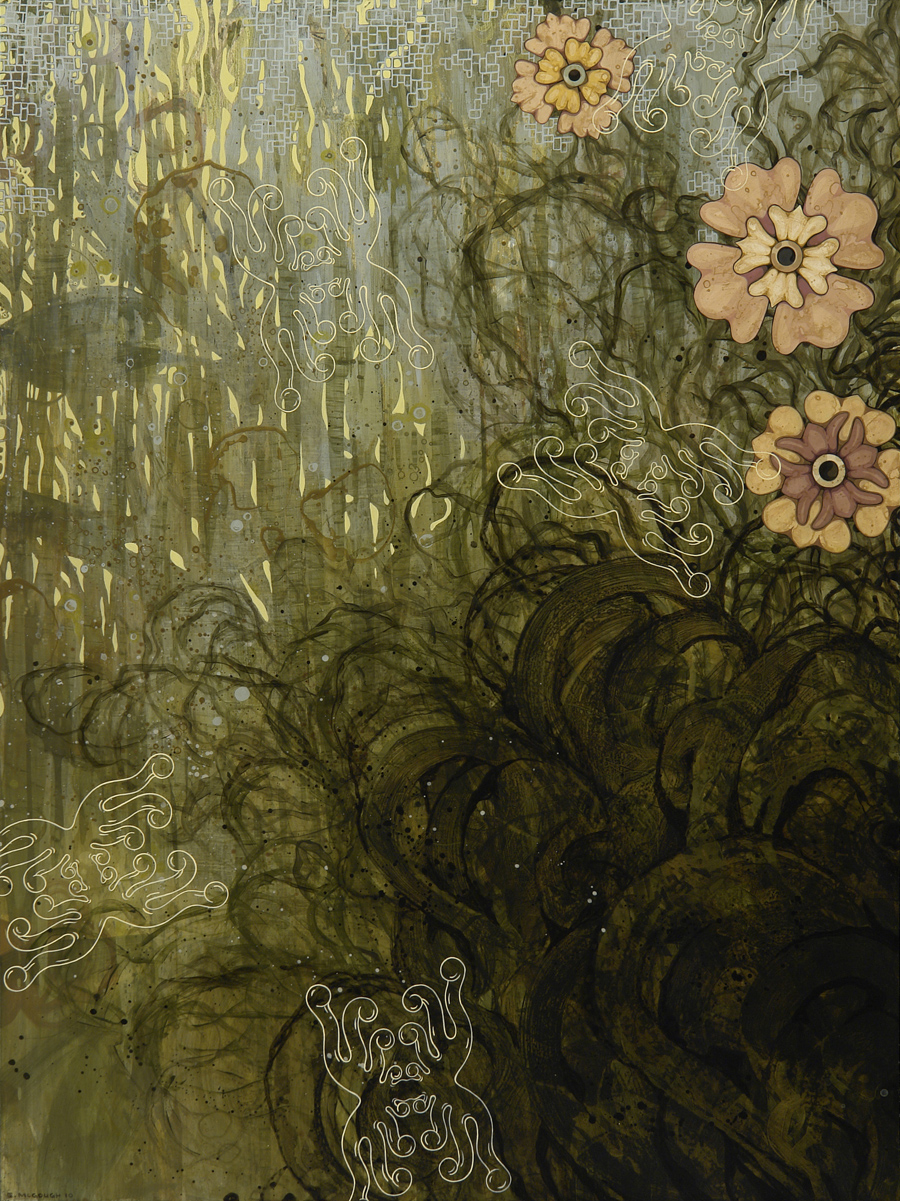

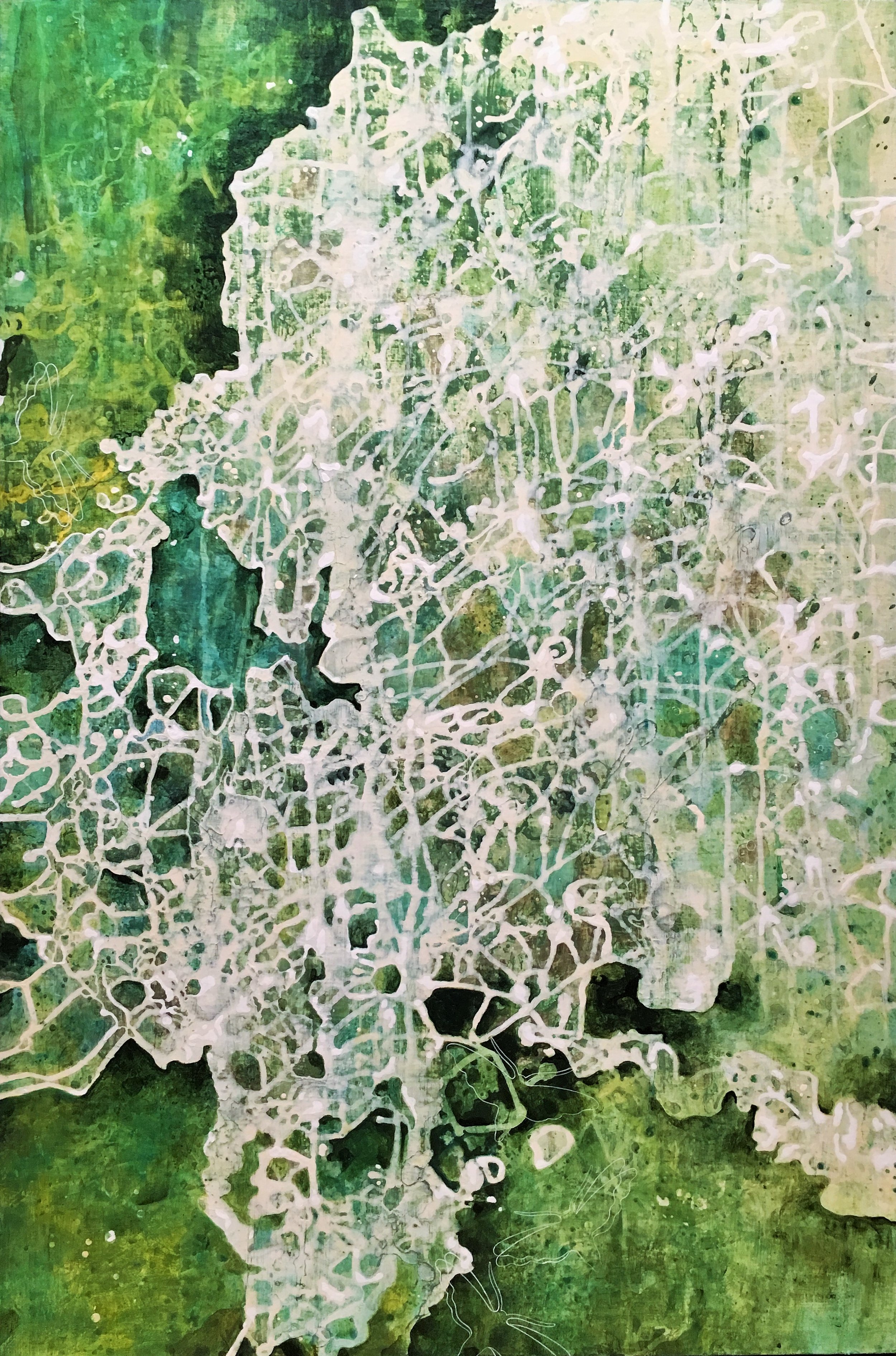

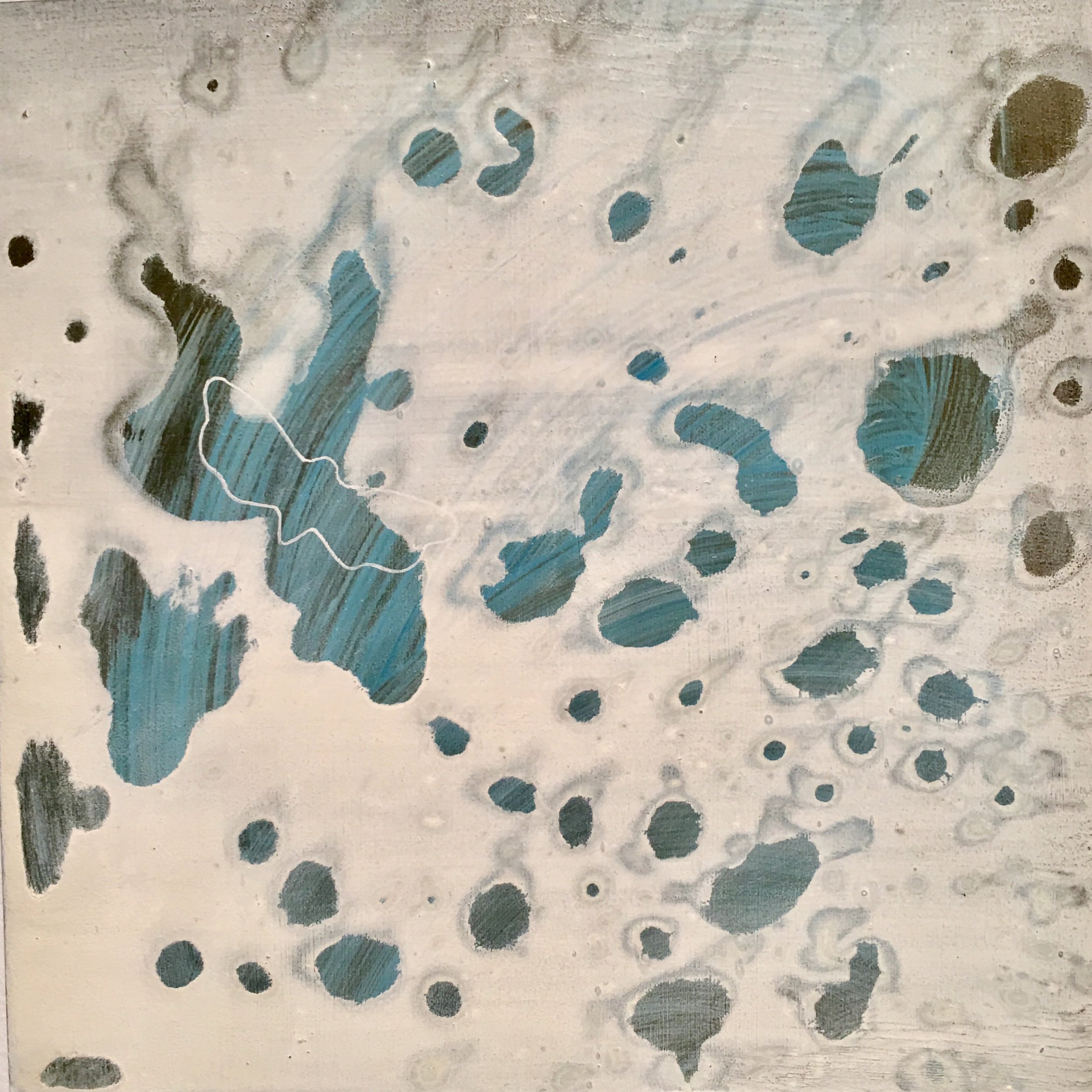

I have been working with utilitarian materials and traditional artist media for nearly two decades. However, working with these materials creates many issues. The British artist Gary Hume explained that the only cathartic aspect of painting occurs when he solved a problem within the process. I agree. I often think of my work as a complex math problem. There is a right answer. The issue is working backward to find the formula that solves the problem. I have for years worked with concrete and oil paint, asphalt and acrylic and fire, fumage and resin. I place these media into forced communication in order to push the conversation between them and possibly add to the overall language.

Where do you get your inspiration for your work?

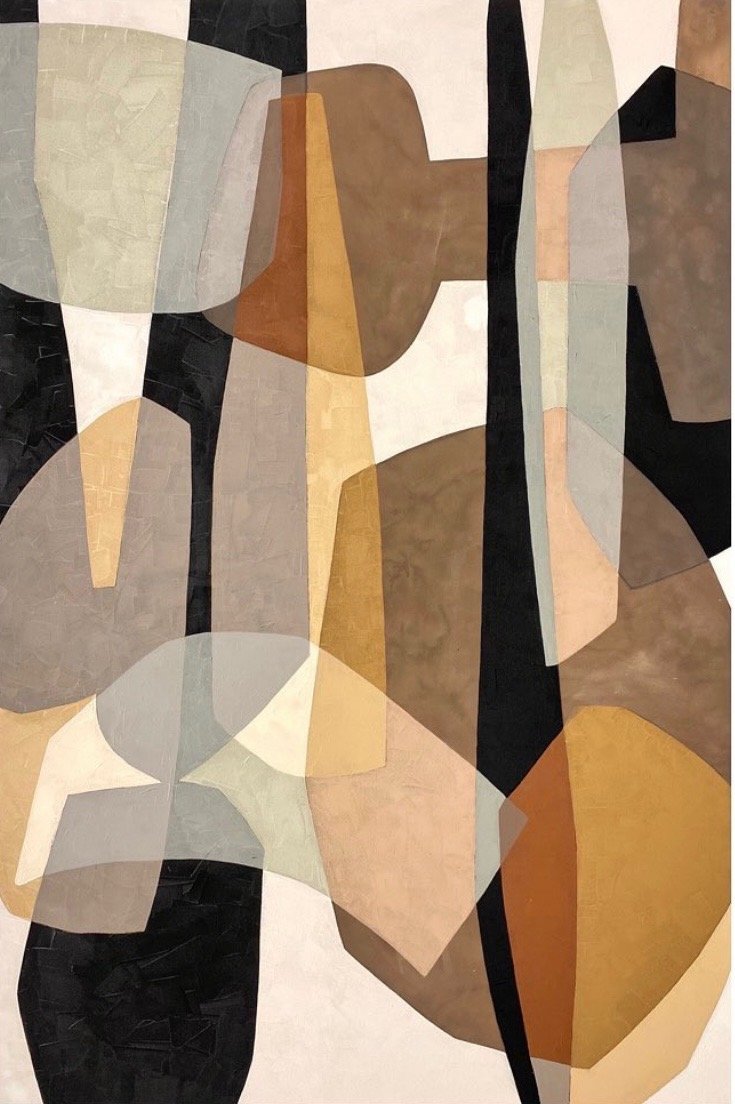

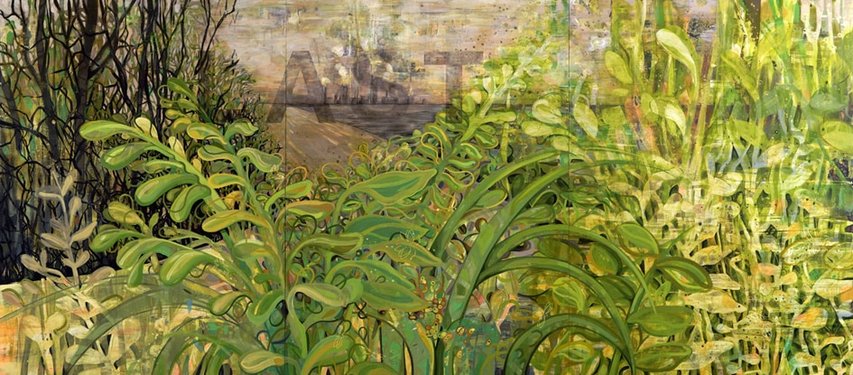

I am greatly influenced by both Eastern philosophy—the acceptance of transience and imperfection—and the urban setting—the physicality and processes found in damage and repair and the building up and wearing down of the surface. I call this influence “urban wabi-sabi.”

I also draw inspiration from the past and from art history. For example, my interest in applying fire to work was sparked by the historic term: Burned-Over District. The term was coined by Charles Grandison Finney in 1876 to describe the earlier religious and reform movements that engulfed western and central New York state. I am also greatly moved by the unintentional mark-making of the prehistoric cave dwellers at Lascaux who scraped their torches against the walls to increase the flames as they made their way deep into the recesses of the cave to create their paintings. Art is a direct physical link to the past.

What is your creative process like?

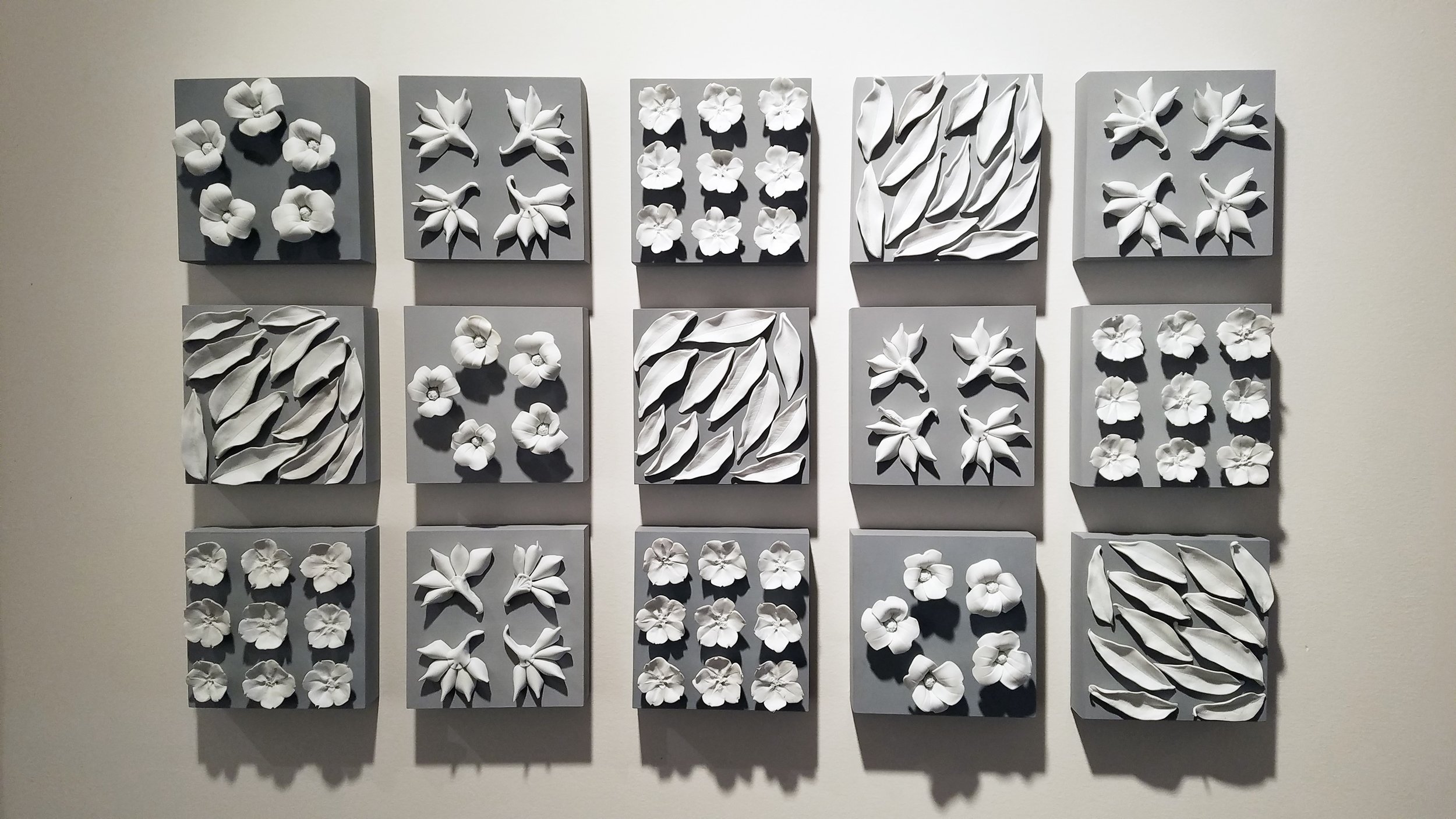

My process involves damage and repair, building up and wearing down. This is the same process that exists in our urban environment. I am fascinated with the beauty and tension caught between that process. Even though my work may look haphazard, I create rules within the process that help guide the work along. This allows me to find the overall balance and challenge the viewer to match what they see to what they know. I want to confront the viewer with materials they see and depend on every day and challenge their view of what is expected of those materials.

What are the most important factors you consider when you create your work?

The first thing I ask myself when I start new work is, what do I know? What do I know from the years of experimenting with non-traditional art materials? What do I know of how these materials interact? What do I know from discoveries made by trial and error? Where do I want to go with this work? I start there and see where I end up.

How has your practice changed over time

I seek to simplify the process, the materials, and the outcome so as to create a greater impact on the outcome.

What do you think is the most difficult aspect of making work? Why?

The most difficult aspect is, to me, also the best aspect. The process is never-ending, but the outcome has to be exceptional.

What part of creating art brings you the most enjoyment?

Often times an abstract artist is asked, “When do you know when a work is done?” There are, possibly, several answers to that question. For me, one of those answers is the work is completed when the piece is engaged by others, especially face-to-face. I believe that when we engage in the art, a kind of positive cycle is enacted between the artist and the viewer. Sharing my art brings me joy.

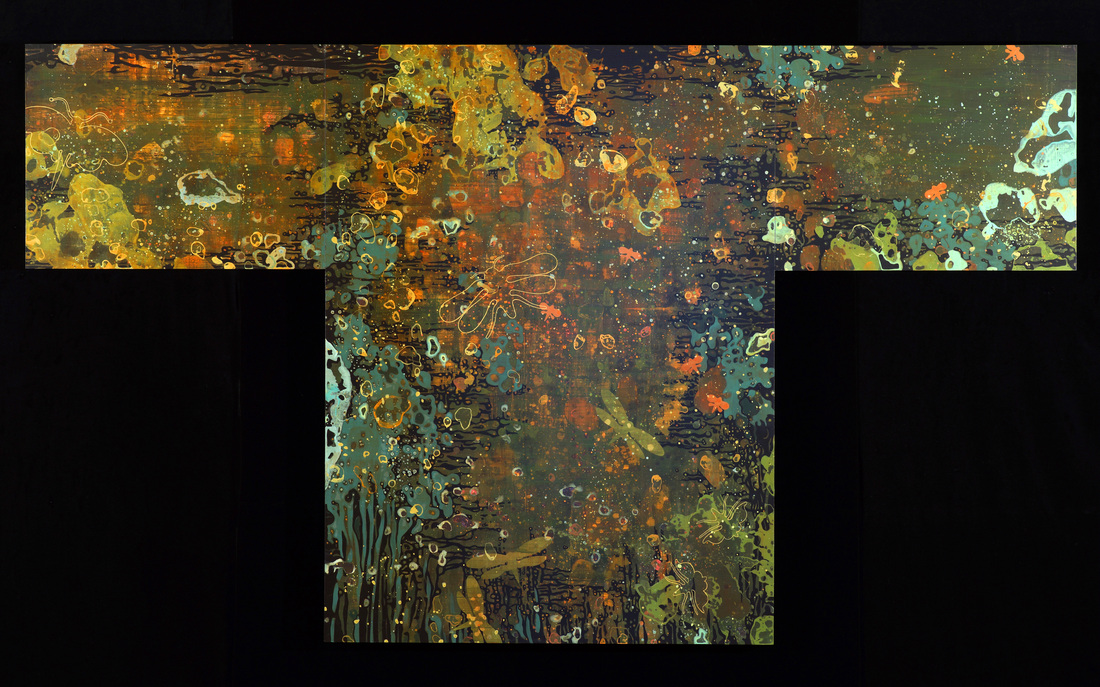

I am working on a new 60x72 that is more in line with (Ir)reverence that has a blue undercoat. Also, there are four more In Search of Lost Glaciers that could be put together to create a larger work. I am also working on a series to diptychs (black and white work with some resin and white oil paint - more to come).

Which of your works is your personal favorite and why?

Within each piece, there is often a section that stands out—a kind of favorite place in the landscape of the work. It serves the work the way an exclamation point serves a sentence. I always try and identify that area within each work—for myself—and look for that exclamation point in the work of others as well.

Of all your travels, which city or place inspires you the most? Why?

Between December 2017 and September 2018, I traveled more than twenty-two-thousand miles across the United States and Canada on an art installation project. I immersed linen works in rivers, forests, grasslands, canyons, and the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Perhaps most influential were the unexpected places that were in the middle of nowhere. Forgettable in a tourist sense, but unforgettable in a larger sense.

What is something quirky or unexpected about you that most people don’t know?

My physical body seems to be attracted to certain bodies of water. When I see water—a small lake, a river, a stream—I often want to submerge myself in it. I have swum in the Arctic Ocean. Skinny dipped in Solitude Lake high up in the Grand Tetons. Bathed in wilderness streams in British Columbia. And plunged into an icy Minnesota lake or two.